In recent decades, the global health and wellness industry has undergone a dramatic transformation. Consumers are increasingly investing in products that promise to support health, longevity, and disease prevention. Two terms frequently encountered in this context are nutraceuticals and dietary supplements. At first glance, they appear interchangeable, and in marketing materials, they are often used loosely. However, in professional, regulatory, and scientific contexts, there are nuanced distinctions between the two. Understanding these differences is not only important for consumers but also essential for brand owners, healthcare professionals, and policymakers navigating this rapidly evolving industry.

The blurred boundaries between nutraceuticals and dietary supplements reflect both consumer demand and industry innovation. As scientific discoveries continue to highlight the health benefits of bioactive compounds, the definitions and applications of these products expand. This creates both opportunities and challenges for regulation, safety, and market growth.

This article provides an in-depth exploration of nutraceuticals and dietary supplements, comparing their definitions, regulatory frameworks, health implications, and market dynamics. It also analyzes how these products are perceived differently across regions, and how businesses can strategically position themselves depending on which segment they operate in.

Defining Nutraceuticals and Dietary Supplements

Dietary Supplements: A Regulatory Category

Dietary supplements are more clearly defined from a regulatory perspective. In the United States, the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994 established a legal framework for products labeled as supplements. According to DSHEA, dietary supplements are intended to supplement the diet and may contain vitamins, minerals, amino acids, herbs, or other botanicals. They are typically available in dosage forms such as tablets, capsules, powders, or liquids.

Unlike conventional foods, supplements are not positioned as full meal replacements, and unlike drugs, they are not permitted to claim disease treatment or cure. However, they can carry structure-function claims (e.g., “supports immune health”) as long as these are truthful and substantiated.

Dietary supplements are therefore firmly grounded in the concept of nutritional support rather than therapeutic intervention. Their regulation varies across jurisdictions, but in most cases, they fall into a category separate from pharmaceuticals.

1.Nutraceuticals: A Broader, Loosely Defined Concept

The term nutraceutical is less rigidly defined and lacks a universally accepted regulatory framework. Coined in the late 1980s by Dr. Stephen DeFelice, “nutraceutical” combines “nutrition” and “pharmaceutical.” Broadly speaking, nutraceuticals are products derived from food sources that provide health benefits beyond basic nutrition, including the prevention or management of chronic diseases.

Examples include:

-

Functional foods enriched with bioactive compounds (e.g., omega-3 fortified yogurt, plant sterol margarines).

-

Isolated nutrients or phytochemicals used in concentrated form (e.g., resveratrol capsules, curcumin extracts).

-

Specialty formulations that blur the line between food and medicine.

Unlike dietary supplements, nutraceuticals often target specific health conditions or are marketed as having pharmacological effects. They may appear in both supplement dosage forms and functional foods, creating overlap between food technology and biomedical research.

Key Differences at a Glance

| Aspect | Dietary Supplements | Nutraceuticals |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Products intended to supplement the diet with specific nutrients. | Products from food sources that provide additional health benefits beyond basic nutrition. |

| Regulatory Clarity | Clearly regulated (e.g., DSHEA in the U.S., EFSA rules in Europe). | No universally standardized regulation; often overlaps with functional foods and pharmaceuticals. |

| Scope | Primarily vitamins, minerals, botanicals, amino acids, and similar substances. | Includes supplements but extends to functional foods, bioactives, and disease-targeted formulations. |

| Health Claims | Structure-function claims allowed, but no disease cure claims. | Often marketed as preventing or managing conditions; claims vary depending on local regulation. |

| Consumer Perception | Seen as nutritional support and wellness aid. | Seen as “food as medicine” with potential therapeutic value. |

2.Scientific Basis: Bioactivity and Mechanisms of Action

One of the most significant distinctions between nutraceuticals and dietary supplements lies in their scientific underpinnings and mechanisms of action.

Dietary supplements are primarily designed to address deficiencies or maintain adequate nutrient levels. For example, vitamin D supplementation supports calcium absorption and bone health. The scientific rationale here is relatively straightforward: supplementation restores or maintains levels of an essential nutrient, preventing deficiencies such as rickets or scurvy. The biochemical pathways are well-studied, and the goal is largely to “fill the gap” in nutrition.

Nutraceuticals, are often studied for their bioactive compounds that exert effects beyond basic nutrition. For instance, polyphenols in green tea (catechins) have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects at the molecular level, influencing signaling pathways related to oxidative stress and immune response. Similarly, omega-3 fatty acids are not only essential nutrients but, when positioned as nutraceuticals, are studied for their role in modulating inflammation, cardiovascular risk, and even mental health outcomes.

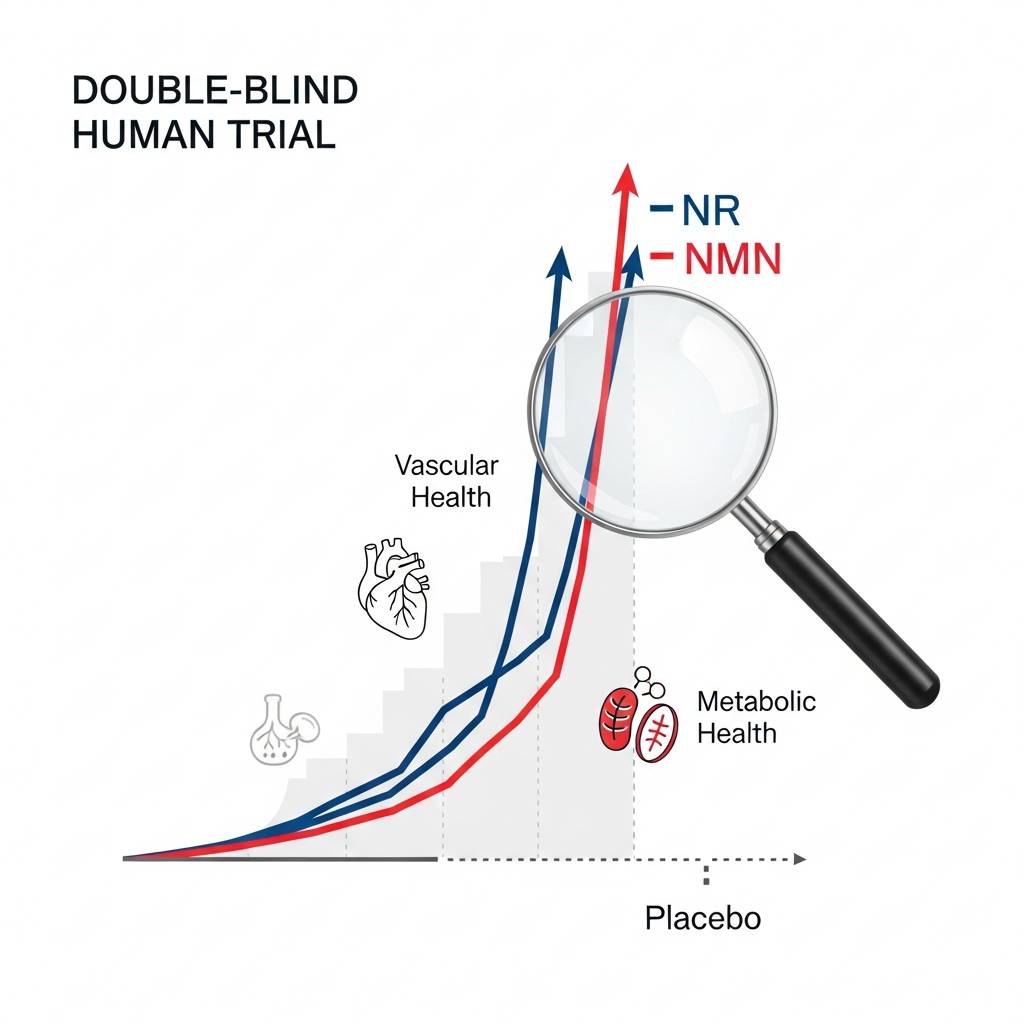

This distinction means that nutraceuticals demand a higher level of scientific validation in terms of mechanistic research, clinical trials, and biomarkers of efficacy. They occupy a middle ground between traditional nutrition and pharmacology, often described as “functional medicine without prescription.”

3.Regulatory Frameworks Across Regions

Another critical difference between the two categories lies in the regulatory environment, which varies widely across regions such as the United States, European Union, Japan, and China.

-

United States:

Dietary supplements are regulated under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA, 1994). Manufacturers are responsible for ensuring safety, but they do not need FDA pre-approval before marketing. Supplements can make structure/function claims (e.g., “supports heart health”) but cannot claim to treat, cure, or prevent diseases. Nutraceuticals, however, do not have a formal regulatory category in the U.S. and are often marketed either as dietary supplements or functional foods. -

European Union:

The EU enforces stricter regulations under the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Health claims for supplements must be scientifically substantiated and approved before marketing. Nutraceuticals are generally classified as functional foods and undergo rigorous safety and efficacy evaluations before health claims are permitted. -

Japan:

Japan pioneered the concept of Foods for Specified Health Uses (FOSHU), which is effectively a nutraceutical category. Products must demonstrate both safety and efficacy through clinical and mechanistic studies before approval. This framework has influenced regulatory trends in other countries. -

China:

China distinguishes between health foods (保健食品) and dietary supplements. Nutraceuticals are often marketed under the health food framework, requiring evidence of functionality and safety. The regulatory system has been tightening in recent years to address quality control and prevent misleading claims.

These regulatory nuances mean that a product labeled as a nutraceutical in one region might only qualify as a dietary supplement in another, underscoring the fluidity and complexity of global classification.

4. Historical and Regulatory Context

One of the reasons why the terms nutraceuticals and dietary supplements are often confused is because they developed in different cultural and regulatory contexts.

-

United States (Dietary Supplement Focus)

In the U.S., the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994 formally established dietary supplements as a unique regulatory category. According to DSHEA, dietary supplements are not drugs, but they can be sold freely as long as they contain dietary ingredients (vitamins, minerals, herbs, amino acids, etc.) and are properly labeled. Manufacturers are not required to prove efficacy before marketing, but they must ensure safety and truthful labeling. This act made the supplement industry highly accessible and allowed for rapid growth. -

Europe (Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals)

In contrast, European markets have historically leaned more toward functional foods and nutraceuticals. While dietary supplements exist in the EU, functional foods (foods enriched with additional health-promoting compounds, such as probiotic yogurts) often dominate. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) regulates health claims strictly, requiring scientific substantiation before a product can claim a benefit. This has led to a stricter environment for nutraceuticals and supplements compared to the U.S. -

Asia (Traditional Medicine and Nutraceutical Integration)

In countries like China, Japan, and India, nutraceuticals are often tied to traditional medicine systems. For example, Japan introduced the category of Foods for Specified Health Uses (FOSHU) in the 1990s, granting approval to certain functional foods and nutraceuticals. India, with its Ayurveda heritage, often considers nutraceuticals as modernized forms of traditional herbal remedies.

The regulatory differences demonstrate why dietary supplement is more commonly used in the U.S., while nutraceutical has broader adoption in global markets, particularly when referring to functional or therapeutic food products.

5. Consumer Perception and Market Positioning

From a consumer perspective, the terms carry different implications:

-

Dietary Supplements are generally perceived as basic health support. Consumers buy them to fill nutrient gaps or maintain daily wellness. They are often affordable, widely available in pharmacies, grocery stores, and online platforms, and marketed toward the general public.

-

Nutraceuticals are viewed as premium health solutions. They are frequently marketed with a stronger emphasis on scientific research, advanced formulations, and potential therapeutic effects. Their branding often targets educated consumers willing to pay more for perceived higher efficacy and innovation.

This positioning difference also influences marketing strategies. Dietary supplements highlight convenience, affordability, and general wellness, while nutraceutical brands highlight cutting-edge science, bioavailability, clinical studies, and targeted benefits.

5. Global Regulatory Frameworks: Nutraceuticals vs. Dietary Supplements

Regulatory perspectives vary widely across the world, and this is where the terminology difference becomes particularly important.

5.1 United States (FDA and DSHEA)

In the U.S., the term “dietary supplement” is formally defined under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994. According to DSHEA:

-

A dietary supplement is intended to supplement the diet.

-

It may contain vitamins, minerals, herbs, amino acids, or other dietary substances.

-

Supplements are regulated as a category of foods, not drugs, meaning they are not required to go through pre-market approval for safety or efficacy.

The term “nutraceutical” is not recognized in U.S. legal or regulatory frameworks. Instead, the FDA focuses on dietary supplements, foods, and drugs. This creates a gray area where companies may market products as nutraceuticals to suggest more advanced health benefits, but legally they are treated as supplements or functional foods.

5.2 European Union (EFSA and Novel Foods Regulation)

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) oversees supplements, functional foods, and health claims.

-

The EU emphasizes evidence-based health claims. For instance, if a product claims “supports immune system function,” the manufacturer must provide scientific evidence to substantiate the statement.

-

The term nutraceutical is not officially recognized in EU legislation either, but functional foods and food supplements are regulated under separate frameworks.

-

The EU has stricter requirements than the U.S. for labeling and health claims.

5.3 India (FSSAI)

India is one of the few countries that formally uses the nutraceutical category in regulation.

-

The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) defines nutraceuticals as naturally occurring compounds with health-promoting, disease-preventing, or medicinal properties.

-

India’s regulation recognizes a separate segment for nutraceuticals apart from dietary supplements, functional foods, and health drinks.

5.4 Japan (FOSHU System)

Japan pioneered the functional foods movement through the Foods for Specified Health Uses (FOSHU) program.

-

Products can obtain a FOSHU approval if scientific evidence shows they support specific physiological functions.

-

Although not directly called “nutraceuticals,” FOSHU foods closely overlap with the concept.

-

Japan also distinguishes between dietary supplements (as foods) and functional products with government-approved claims.

5.5 China

China regulates supplements under the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA).

-

Supplements (保健食品, or health foods) require registration and approval.

-

While nutraceuticals as a separate category are not formally defined, the booming functional foods industry is heavily regulated, especially for imported products.

👉 Key Insight: The term dietary supplement has regulatory recognition globally (with specific definitions in the U.S. and EU), whereas nutraceutical is often used in marketing, research, or country-specific regulations (India, partly Japan). This creates challenges in global product positioning and labeling.

6. Industry Applications and Market Trends

6.1 Consumer Awareness and Demand

-

Consumers increasingly seek preventive health solutions rather than waiting for disease onset.

-

Nutraceuticals are often marketed with broader lifestyle benefits (anti-aging, metabolic health, gut health).

-

Dietary supplements are more straightforward, filling nutrient gaps in daily diets.

6.2 Market Growth

-

The global dietary supplement market is projected to grow steadily due to aging populations, rising chronic diseases, and lifestyle factors.

-

The nutraceuticals sector often overlaps but sees faster growth in areas like functional beverages, probiotic yogurts, plant-based formulations, and personalized nutrition.

6.3 Scientific Innovation

-

Nutraceuticals rely on biotechnology, nanoencapsulation, and targeted delivery systems to enhance bioavailability.

-

Dietary supplements are increasingly adopting clean-label and sustainable sourcing trends but remain relatively simpler in formulation.

6.4 Retail and Distribution

-

Dietary supplements dominate pharmacy shelves, online marketplaces (Amazon, iHerb), and retail chains.

-

Nutraceuticals often appear in premium health stores, direct-to-consumer wellness brands, and functional food/beverage sectors.

6. Consumer Perception and Market Challenges

While nutraceuticals and dietary supplements both contribute significantly to health promotion, their coexistence in the marketplace also presents a set of challenges for consumers, manufacturers, and regulators. Understanding these challenges provides insight into why differentiation between the two categories matters not just academically but also practically.

6.1 Consumer Confusion and Overlap

One of the most common issues is the overlap in product claims. For instance, a capsule containing turmeric extract can be marketed as a dietary supplement in the U.S., while in Japan or parts of the EU, it may be marketed as a nutraceutical with specific health claims. To the average consumer, the distinction is unclear, and the terms are often used interchangeably.

-

Impact: This can lead to difficulty in comparing products, making informed purchasing decisions, or even trusting marketing messages.

-

Solution: Transparent labeling and education initiatives are essential. Clear differentiation in terms of intended use (nutrition vs. therapeutic support) would help reduce confusion.

6.2 Quality and Standardization Issues

Nutraceuticals, being more closely tied to medicinal properties, often demand higher standards of standardization and purity. However, dietary supplements—particularly in markets with looser regulations—may vary widely in quality.

-

Example: Omega-3 fish oil supplements may differ significantly in purity, oxidation level, or EPA/DHA concentration, depending on whether the manufacturer adheres to pharmaceutical-grade quality or just baseline dietary supplement regulations.

-

Implication for Industry: Companies that aim to position themselves as nutraceutical providers often invest heavily in R&D, clinical trials, and third-party testing, which elevates costs but enhances credibility.

6.3 Regulatory Uncertainty and Global Trade

In an increasingly globalized marketplace, manufacturers often face regulatory mismatches when exporting products.

-

Case Example: A U.S. dietary supplement company entering the EU must reformulate or reclassify certain products to meet EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) requirements. Ingredients like melatonin, commonly sold as a supplement in the U.S., may be classified as a prescription-only medicine in Europe.

-

Result: This creates barriers to market entry, higher compliance costs, and sometimes even reformulation of products to meet local definitions of “nutraceutical” or “dietary supplement.”

6.4 Marketing and Ethical Considerations

Both nutraceutical and dietary supplement industries often face criticism over marketing practices. Some products are promoted with exaggerated claims or vague promises such as “boosts immunity” or “supports longevity,” which lack substantiated evidence.

-

Consumer Impact: Overpromising without sufficient evidence can erode trust and contribute to skepticism, even toward credible, clinically validated products.

-

Industry Response: Responsible manufacturers and nutraceutical leaders increasingly use evidence-based marketing, citing peer-reviewed studies, clinical trial outcomes, and clear disclaimers to ensure compliance and maintain credibility.

7. Regulatory Framework: Legal Classifications and Implications

Perhaps the most defining difference between nutraceuticals and dietary supplements lies in how they are classified and regulated across different jurisdictions. Regulatory frameworks not only dictate what can be marketed but also influence consumer perception, clinical research funding, and industry growth.

7.1 United States

In the U.S., dietary supplements are defined and regulated under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994. According to DSHEA, dietary supplements:

-

Must contain one or more dietary ingredients (vitamins, minerals, amino acids, herbs, or botanicals).

-

Are regulated as a category of food, not as drugs.

-

Cannot make claims to "diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease," but can make structure/function claims (e.g., “supports immune health”).

-

Do not require pre-market approval by the FDA, though manufacturers are responsible for ensuring safety.

Nutraceuticals, however, remain a grey area in U.S. regulation. The FDA does not officially recognize “nutraceutical” as a regulatory category. Depending on formulation and intended claims, nutraceuticals may fall under:

-

Food (if presented as functional food or beverage).

-

Dietary supplement (if marketed in pill/capsule/powder format).

-

Drug (if disease claims are made, requiring clinical trials and FDA approval).

This ambiguity often benefits companies wanting to market beyond the restrictions of dietary supplement regulations, though it also presents compliance risks.

7.2 European Union

In the European Union, regulation is stricter compared to the U.S. Dietary supplements fall under the Food Supplements Directive (2002/46/EC), which limits the forms of nutrients that may be included, with maximum permitted levels for vitamins and minerals. Claims are regulated by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which approves only scientifically substantiated health claims.

The term “nutraceutical” is not officially recognized under EU law either. Products with medicinal claims are classified as medicinal products and must undergo pharmaceutical-level approval processes. However, functional foods (such as probiotic yogurts or cholesterol-lowering margarines) may be marketed with approved health claims, placing them closer to the nutraceutical concept.

7.3 Asia-Pacific and Emerging Markets

-

Japan: Pioneered the concept of “Foods for Specified Health Uses” (FOSHU), an official regulatory framework that aligns closely with nutraceuticals. Products with scientifically validated health benefits receive a FOSHU seal.

-

India: The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) recognizes nutraceuticals as a distinct category, requiring adherence to specific standards for labeling, permissible ingredients, and health claims.

-

China: Has established a “Health Food” category, encompassing both dietary supplements and certain functional nutraceuticals. Pre-market approval is required, and clinical evidence is often mandatory for claims.

7.4 Implications of Regulatory Disparities

The lack of global consensus on definitions creates both opportunities and challenges:

-

Companies can position products flexibly depending on market entry strategies.

-

Variations in standards make international expansion more complex.

-

Consumers face confusion due to inconsistent terminology and claims.

From a scientific and industrial perspective, the nutraceutical category represents a bridge between food and medicine, but regulatory authorities worldwide continue to debate how to classify and control it effectively.

8. Where Nutraceuticals and Dietary Supplements Are Heading

The line between nutraceuticals and dietary supplements will likely continue to blur in the coming years, but certain emerging trends will shape how they are defined, regulated, and consumed.

8.1 Scientific Innovation and Personalized Nutrition

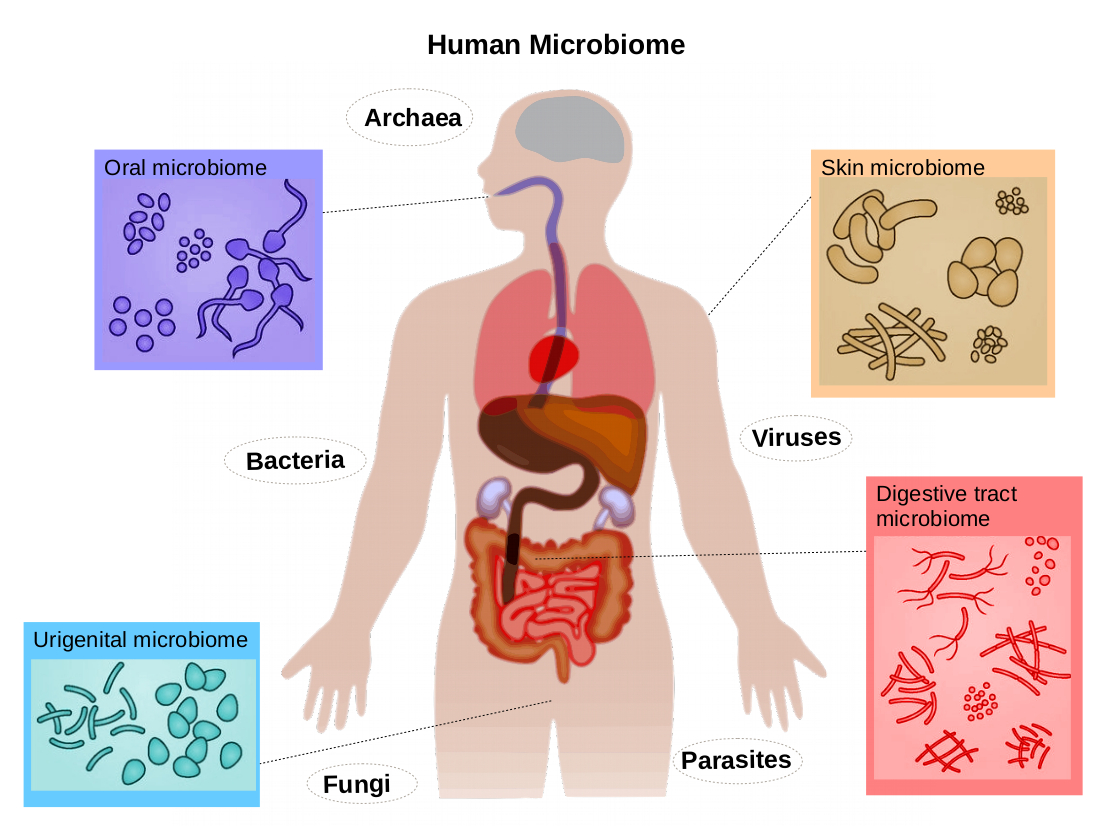

Advances in genomics, metabolomics, and microbiome research are moving both industries toward personalized health solutions. Nutraceuticals, with their food-based origins, may increasingly integrate into functional diets tailored to an individual’s genetic and metabolic profile. Dietary supplements, meanwhile, are likely to adopt precision formulations, where vitamins, minerals, and compounds are customized based on biomarker analysis or real-time health tracking.

8.2 Regulatory Evolution

Globally, regulatory bodies are reconsidering how to categorize these products. For example:

-

United States: Supplements remain regulated under DSHEA, but FDA scrutiny on structure/function claims and post-market safety is tightening.

-

European Union: Nutraceuticals still lack an official category, but EFSA is applying stricter scientific criteria for health claims.

-

Asia (Japan, China, India): Functional foods and traditional nutraceuticals are gaining clearer definitions, often integrated with traditional medicine systems.

This evolution suggests that nutraceuticals may receive a more formal regulatory identity in the future, narrowing the definitional gap with supplements.

8.3 Integration with Technology

Wearables, AI-driven diet apps, and digital health platforms are creating a bridge between consumer data and supplement/nutraceutical choices. For example, smart apps may recommend a nutraceutical beverage enriched with adaptogens for stress management or a supplement pack with omega-3 and vitamin D after analyzing dietary intake logs.

8.4 Consumer Demand Shifts

Modern consumers increasingly demand sustainability, transparency, and scientific validation. Nutraceuticals, with their “food-first” narrative, align well with clean-label and natural product trends. Supplements, however, are innovating with novel delivery systems (gummies, powders, effervescent tablets, and even nanotechnology-based capsules) to improve compliance and absorption.

8.5 Convergence of the Two Worlds

While historically distinct, nutraceuticals and dietary supplements are converging toward a holistic preventive healthcare model. Future products may not fit neatly into either category—consider:

-

Hybrid solutions like probiotic chocolates, fortified beverages, or personalized sachets containing both botanicals and micronutrients.

-

Functional medical nutrition, where nutraceuticals and supplements combine with clinical nutrition to address chronic diseases such as diabetes or cardiovascular conditions.

Consumer Perceptions and Market Confusion

One of the biggest challenges in distinguishing nutraceuticals from dietary supplements lies in consumer perception. Surveys consistently show that many people use these terms interchangeably, often unaware of the nuanced differences. For instance:

-

“Nutraceutical” is sometimes perceived as a more scientific or premium term, associated with products sold in health food stores, wellness clinics, or recommended by practitioners.

-

“Dietary supplement”, on the other hand, is often seen as the standard over-the-counter capsule, gummy, or powder that provides vitamins and minerals.

This confusion has important implications:

-

Marketing strategies often emphasize the nutraceutical label to create a perception of higher efficacy or innovation. Brands may highlight clinical research, bioactive compounds, or advanced delivery systems to position products as nutraceuticals rather than generic supplements.

-

Consumer trust can be impacted by terminology. In markets like the United States, where “dietary supplement” is highly regulated, some consumers may trust the transparency and safety oversight of supplements more than unregulated nutraceutical claims.

-

Purchasing behavior shows that individuals seeking prevention or general wellness are more inclined toward dietary supplements (e.g., multivitamins, fish oil), while those addressing specific health concerns (e.g., joint pain, cognitive decline) may gravitate toward nutraceuticals promising targeted therapeutic support.

This blurred line creates both opportunities and risks for manufacturers. On one hand, nutraceutical branding can differentiate products in a crowded market; on the other, overpromising benefits risks regulatory scrutiny and consumer disappointment.

Scientific Foundations and Clinical Evidence

Another critical distinction between nutraceuticals and dietary supplements lies in the degree of scientific substantiation supporting product claims.

-

Dietary Supplements

Many supplements rely on established nutrition science. The benefits of vitamin D for bone health, or omega-3 fatty acids for heart health, are widely recognized and supported by large-scale epidemiological studies. However, not all supplements have robust evidence — some remain popular based on tradition or emerging but inconclusive findings. -

Nutraceuticals

By contrast, nutraceuticals are often marketed on the basis of functional food science and bioactive compound research. Examples include:-

Curcumin: Extracted from turmeric, studied for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

-

Resveratrol: Found in grapes and red wine, linked to cardiovascular health and longevity.

-

Probiotics: Live microorganisms researched for gut microbiota balance and immune support.

-

What differentiates nutraceuticals is not simply the compound but the delivery system and therapeutic positioning. For example, a standard vitamin C supplement is considered a dietary supplement. However, a specialized nano-encapsulated vitamin C designed for targeted immune modulation might be marketed as a nutraceutical.

The challenge here is that while nutraceuticals lean heavily on innovation and bioactive science, the clinical evidence is not always as strong or consistent as it is for established nutrients. Regulatory agencies, including the FDA and EFSA, have repeatedly warned against exaggerated claims in nutraceutical marketing.

References

-

National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. (n.d.). Dietary Supplement Fact Sheets.

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Dietary Supplement Labeling Guide & Regulatory Framework.

-

European Food Safety Authority. (n.d.). Guidance on Nutraceuticals and Food Supplements.

-

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine Reports.

-

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (n.d.). Research on Dietary Supplements and Health Outcomes.

-

Journal of Dietary Supplements. (n.d.). Peer-reviewed studies on nutraceuticals and supplement science.

-

MDPI. (n.d.). Nutrients Journal – Nutraceuticals and Dietary Supplement Research.