1. What Are Probiotics? A Scientific, Strain-Level Definition

Although the word “probiotics” has become widely popular in consumer products, the scientific definition is far more specific and restrictive than most people realize. According to the FAO/WHO, probiotics are live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host. Each part of this definition has real scientific weight.

Probiotics must be alive when consumed. This seems obvious, but many commercial products fail to guarantee survival through manufacturing, transportation, and storage. The biological activity of a probiotic depends on its ability to endure harsh gastric conditions—such as stomach acid, bile salts, and digestive enzymes—before reaching the intestines alive. Dead bacteria or postbiotic fragments can still have some physiological effects, but they cannot be classified as probiotics under the strict definition.

Probiotics must be taken at adequate doses, commonly measured in CFU (colony-forming units). Different strains require different minimum thresholds to produce measurable effects. A product boasting “millions of live bacteria” is essentially useless; meaningful clinical effects are typically observed in the billions.

And most importantly—probiotics must be defined at the strain level. This means the full scientific name should include genus, species, and an alphanumeric strain code. For example:

-

Lactobacillus rhamnosus = species

-

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103) = specific strain with proven benefits

Two organisms may share the same genus and species but behave like completely different biological entities if they have different strain identifiers. This is why claims such as “Lactobacillus improves digestion” are scientifically meaningless. Only strain-specific evidence can establish a real health benefit.

To put it simply:The strain number is the difference between a scientifically validated probiotic and just another random bacteria.

This level of precision is what separates high-quality probiotic supplements from vague “live culture” products or fermented foods that do not undergo controlled clinical testing.

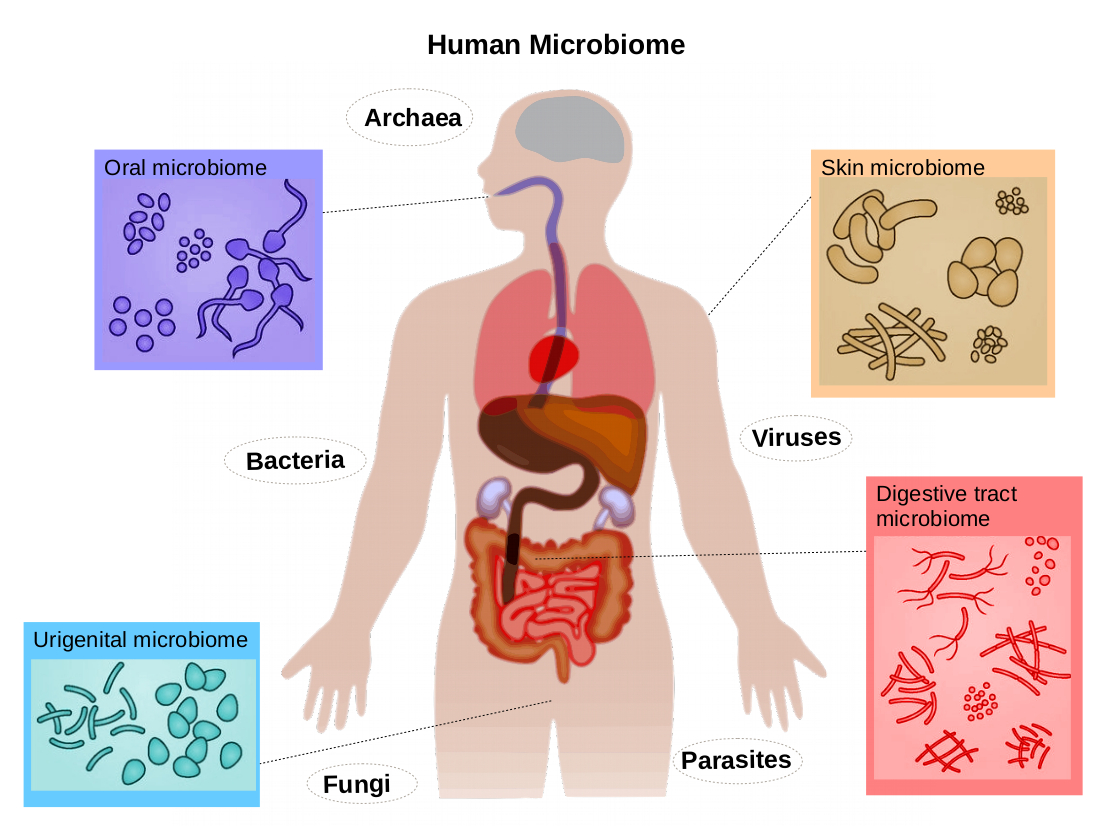

2. The Human Microbiome: The Ecosystem Probiotics Support

To understand what probiotics do, we must first understand the system they interact with: the human microbiome. The human gut alone contains trillions of microorganisms—bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea—forming a complex ecological community far larger than the number of human cells in your entire body. This ecosystem is dynamic, diverse, and deeply integrated into human physiology.

The gut microbiome participates in hundreds of critical functions:

-

Digesting dietary fibers that human enzymes cannot break down

-

Producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that feed colon cells

-

Synthesizing vitamins such as vitamin K and some B-vitamins

-

Training the immune system to distinguish threats from harmless stimuli

-

Regulating inflammation across the entire body

-

Communicating with the brain through neural, hormonal, and biochemical signals

-

Influencing metabolism, blood sugar, lipid levels, and fat storage

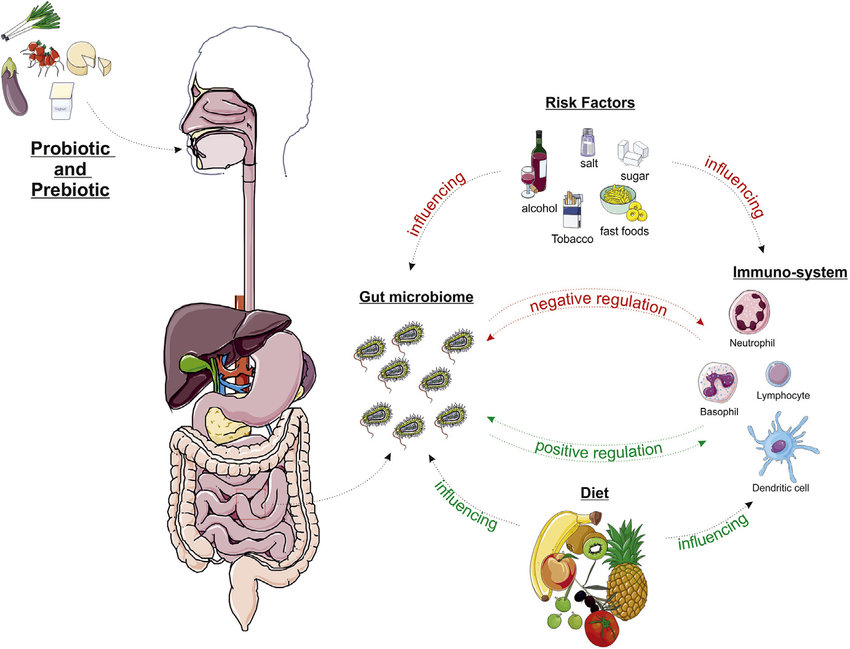

A healthy gut ecosystem is like a thriving forest—highly diverse, balanced, and resilient. But modern lifestyles can easily disrupt this equilibrium. A diet heavy in ultra-processed food, chronic stress, poor sleep, antibiotic usage, alcohol consumption, or gastrointestinal infections can all cause dysbiosis, meaning an imbalance in microbial composition.

Dysbiosis isn’t a minor issue; it is now linked with:

-

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

-

Inflammatory bowel conditions

-

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

-

Anxiety, depression, and cognitive changes

-

Skin issues such as eczema, acne, and rosacea

-

Allergies and autoimmune reactions

Within this framework, probiotics function not as “magic bullets” but as biological tools designed to help restore ecological balance. They cannot fix everything on their own, but when selected correctly, they influence this complex environment in ways that meaningfully support human health.

3. How Probiotics Work: Detailed Mechanisms

Most basic articles summarize probiotic mechanisms with one sentence:“Probiotics help restore gut balance and support immunity.”

This is oversimplified to the point of being misleading. Below is a full, mechanism-by-mechanism breakdown, written at the level of someone designing formulas—not someone browsing a supermarket shelf.

Competitive Exclusion — Probiotics Take Up “Real Estate” Before Pathogens Do

In the gut, microbes compete for physical space on the intestinal lining. This surface is limited, meaning whichever organisms attach first gain the upper hand. Certain probiotic strains possess specialized adhesion proteins that allow them to anchor themselves more effectively than harmful bacteria.

By occupying these attachment sites, probiotics prevent pathogenic species from establishing colonies, a phenomenon known as competitive exclusion.

Why this matters:

-

Reduces pathogenic overgrowth

-

Protects against post-antibiotic disturbances

-

Minimizes episodes of diarrhea or traveler’s digestive issues

This mechanism is especially important immediately after antibiotic treatment, when microbial “real estate” is wide open for recolonization.

Producing Organic Acids — Creating an Environment Harmful to Bad Bacteria

Many Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains ferment carbohydrates to produce lactic acid, acetic acid, and other metabolites that lower the pH of the gut environment.

Pathogenic bacteria—such as E. coli, Clostridium, and Salmonella—prefer a more alkaline environment, so a mildly acidic gut restricts their proliferation.

This acidification:

-

Improves nutrient absorption

-

Enhances mineral solubility

-

Limits growth of harmful microbes

-

Supports healthier microbial succession

In practice, this means probiotics do not “kill” harmful bacteria like antibiotics do—they outcompete and starve them by altering the environment.

Immune Modulation — Probiotics Don’t Boost Immunity; They Balance It

The gut is the largest immune organ in the human body. Around 70% of immune cells reside in the gastrointestinal tract. Probiotics interact with immune cells through pattern recognition receptors, cytokine signaling, and molecular byproducts.

But probiotics do not simply “boost immunity.”

They act as immune modulators, which means:

-

Enhancing underactive immunity

-

Calming overactive, inflammatory responses

-

Improving IgA secretion at the mucosal surface

-

Fine-tuning T-cell responses to reduce hypersensitivity

This dual effect explains why probiotics are useful in conditions that appear contradictory:

-

Supporting resistance to infections

-

Easing eczema and allergy symptoms

-

Maintaining immune balance during stress

It is all part of the same regulatory mechanism—not a contradictory effect.

Strengthening the Intestinal Barrier — Protecting Against “Leaky Gut”

The intestinal barrier is held together by proteins called tight junctions, which regulate what is allowed to enter the bloodstream. When this barrier becomes weakened—due to stress, toxins, inflammation, poor diet, or alcohol—particles that should remain inside the gut leak into systemic circulation. This triggers chronic low-grade inflammation, often called metabolic endotoxemia.

Certain probiotic strains have been shown to:

-

Increase tight-junction protein expression

-

Stimulate mucin production

-

Support epithelial regeneration

-

Reduce permeability (“leaky gut”)

A healthier intestinal barrier not only improves digestion but also reduces systemic inflammation, impacting skin health, metabolic stability, and even mood.

Enhancing SCFA Production — Fuel for Colon Cells and Long-Term Health

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), especially butyrate, are produced when gut bacteria ferment fibers and prebiotics. Butyrate:

-

Is the primary energy source for colon cells

-

Reduces inflammation

-

Improves metabolic function

-

Supports insulin sensitivity

-

Affects neurotransmitter synthesis

-

Helps regulate appetite and satiety

Probiotics often work in tandem with dietary fiber:

They help ferment fibers more efficiently, increasing SCFA yield. This is one reason synbiotics (probiotics + prebiotics) are often more effective than probiotics alone.

Gut–Brain Axis — How Microbes Influence Mood, Stress, and Sleep

The gut produces approximately 90% of the body’s serotonin, and microbial metabolites influence neurotransmitter pathways, the vagus nerve, and inflammatory channels—three of the strongest drivers of mental and emotional health.

Certain strains (e.g., Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) have been shown to:

-

Reduce cortisol

-

Improve stress resilience

-

Support sleep quality

-

Influence emotional processing

This area of research is known as psychobiotics, one of the most rapidly developing fields in microbiome science.

Metabolic Regulation — The Microbial Link to Weight & Blood Sugar

Probiotics influence metabolism indirectly through:

-

Reducing gut permeability → less inflammation

-

Modulating hormones like GLP-1

-

Affecting fat absorption efficiency

-

Regulating bile acid metabolism

-

Influencing the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio

Probiotics alone do not cause dramatic weight loss, but they contribute to a metabolic environment that favors:

-

Better glucose control

-

Reduced inflammation

-

Lower visceral fat accumulation

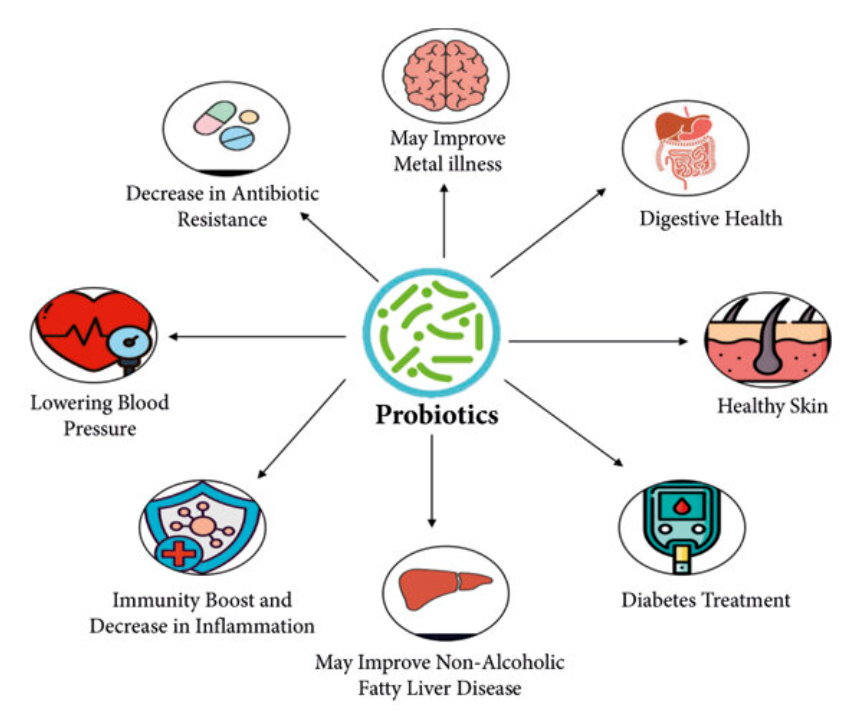

Clinical Benefits of Probiotics

Probiotics influence human health across a wide spectrum of physiological systems. Their effects are highly strain-specific, meaning each strain has different mechanisms, clinical evidence, and therapeutic value. Below is a comprehensive, category-by-category breakdown of probiotic benefits, written with medical-grade detail and practical relevance for supplement brands and consumers alike.

1. Digestive Health: The Most Established and Broadly Studied Benefit

Digestive health remains the most scientifically validated application of probiotics because the gut microbiota directly influences motility, nutrient absorption, immune activity, and mucosal integrity. Dysbiosis—often caused by antibiotics, stress, poor diet, infection, or chronic inflammation—can manifest as constipation, diarrhea, bloating, abdominal pain, or irregular bowel movements.

Probiotics promote digestive stability through several mechanisms: regulating motility, displacing gas-producing microbes, strengthening mucosal barriers, reducing inflammation, and restoring microbial diversity.

1.1 Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

IBS affects millions worldwide and involves a complex interplay of visceral hypersensitivity, immune activation, dysbiosis, and stress.

Multiple RCTs demonstrate that specific strains can improve IBS symptoms by:

-

reducing abdominal pain

-

improving bowel regularity

-

decreasing bloating

-

modulating inflammatory biomarkers

Highly studied strains include:

-

Lactobacillus plantarum 299v – improves abdominal pain and gas tolerance

-

Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 – reduces bloating, pain, and bowel irregularity

-

Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 – reduces diarrhea-predominant IBS symptoms

These strains act through anti-inflammatory activity, SCFA enhancement, and host immune modulation.

1.2 Constipation (Functional Constipation & Slow Transit)

Constipation frequently arises from inadequate SCFA production, impaired motility, or reduced microbial diversity.

Probiotics can stimulate peristalsis by producing metabolites that interact with the enteric nervous system.

Strains with strong evidence:

-

Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12 – increases stool frequency & improves stool form

-

Lactobacillus casei Shirota – enhances motility and reduces intestinal transit time

-

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG – helpful for both adults and children

Probiotics often work synergistically with prebiotics (FOS, inulin) to improve bowel habits.

1.3 Diarrhea, Including Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea (AAD)

One of the most proven clinical uses of probiotics is preventing AAD, where antibiotics disrupt normal gut flora and enable opportunistic pathogens to proliferate.

Best-studied strains include:

-

Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 – gold-standard for AAD prevention

-

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG – reduces incidence and duration

-

Bifidobacterium breve Yakult strain – stabilizes microbial balance during antibiotic therapy

These strains exhibit pathogen inhibition, immune signaling normalization, and toxin neutralization activities.

1.4 Bloating, Gas, and Dyspepsia

Gas production and abdominal distension often result from fermentation imbalances or transient microbiota shifts.

Useful strains:

-

Lactobacillus plantarum 299v

-

Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 – reduces visceral hypersensitivity

-

Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM

These strains improve gas tolerance, reduce fermentation stress, and improve mucosal resilience.

2. Immune Support: Balancing, Not “Boosting” Immunity

The immune system and gut microbiota exist in constant dialogue. Probiotics influence immunity by modulating inflammatory pathways, improving mucosal antibody defense, and stabilizing gut-immune signaling. Rather than “strengthening immunity” indiscriminately, probiotics optimize immune response, reducing excessive inflammation while enhancing pathogen resistance.

Key immune benefits include:

-

Reduced frequency and severity of common colds

-

Improved mucosal IgA secretion

-

Less inflammation in the GI tract

-

Faster recovery from infections

-

Enhanced response to vaccines in certain populations

Strains with evidence:

-

Lactobacillus paracasei CASEI 431 – improves immune response to vaccines

-

Bifidobacterium animalis BB-12 – enhances mucosal immunity

-

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG – reduces respiratory infections in children

-

Lactobacillus casei Shirota – modulates NK cell activity

These strains do not stimulate the immune system aggressively; they guide it toward balance—reducing unnecessary overactivation while enhancing frontline defense.

3. Women’s Health: Vaginal Microbiome & Urinary Tract Support

The female vaginal microbiome is dominated by Lactobacillus species, which maintain an acidic environment (optimal pH ≈ 4.5) through lactic acid production. Stress, hormonal changes, antibiotics, and sexual activity can disrupt this ecosystem, increasing risk of bacterial vaginosis, yeast infections, and urinary discomfort.

Probiotics support women’s health by:

-

Restoring Lactobacillus dominance

-

Lowering vaginal pH

-

Producing hydrogen peroxide to inhibit pathogens

-

Strengthening mucosal barriers

-

Reducing recurrence of bacterial vaginosis (BV)

Clinically significant strains:

-

Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05 – gold-standard for vaginal microbiome restoration

-

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 + Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14 – synergistic pair widely validated in studies

-

Lactobacillus jensenii – supports mucosal integrity

These strains can be taken orally or administered intravaginally depending on clinical context.

4. Skin Health: The Gut–Skin Axis

The skin and gut share strong immunological and metabolic connections. Dysbiosis can increase systemic inflammation, weaken the epithelial barrier, and promote conditions such as acne, eczema, and redness.

Probiotics may benefit the skin by:

-

Reducing inflammatory cytokines

-

Supporting gut barrier integrity

-

Modulating sebum production

-

Balancing microbial metabolites associated with skin flare-ups

-

Improving the skin’s moisture retention

Strains involved in skin benefits:

-

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG – reduces eczema risk in infants and children

-

Bifidobacterium longum – decreases sensitivity and inflammation

-

Lactobacillus paracasei ST11 – helps skin barrier and hydration

While probiotics are not a cure-all, they support internal balance that reflects outwardly on skin health.

5. The Gut–Brain Axis: Probiotics for Mood, Stress & Cognitive Function

One of the most exciting and rapidly evolving areas of probiotic research is the microbiota-gut-brain axis, a communication network involving the vagus nerve, neurotransmitters, immune signaling, and microbial metabolites.

Dysbiosis is now recognized as a contributing factor to:

-

Anxiety

-

Stress sensitivity

-

Poor sleep

-

Cognitive fog

-

Mild depressive symptoms

Psychobiotic strains with evidence include:

-

Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 + Bifidobacterium longum R0175 – reduce cortisol & improve stress response

-

Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 – improves emotional processing

-

Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 – emerging evidence for mood regulation

These strains influence serotonin pathways, GABA signaling, inflammation, and the vagus nerve.

6. Probiotics for Metabolic Health and Weight Management

Although probiotics are not weight-loss drugs, they impact metabolic regulation through several pathways:

-

Reducing gut permeability (lowering systemic inflammation)

-

Modulating GLP-1 and appetite hormones

-

Affecting triglyceride metabolism

-

Influencing fat storage and energy expenditure

-

Supporting better blood sugar control

Prominent strains:

-

Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 – associated with reduced visceral fat

-

Bifidobacterium breve B-3 – linked to improved body composition

-

Lactobacillus plantarum strains – support metabolic balance

These effects are modest but meaningful when combined with diet and lifestyle interventions.

7. Probiotics Across Life Stages: Infants, Adults & Seniors

Infants

The first 1000 days of life are critical for microbiome formation.

Probiotics may help:

-

Reduce colic

-

Improve stool regularity

-

Lower eczema risk

-

Support immune development

Best strains: Bifidobacterium infantis, B. breve, Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938.

Adults

Supports digestive stability, stress response, metabolic function, and immune balance.

Seniors

Aging is associated with reduced microbial diversity.

Probiotics may help:

-

Improve regularity

-

Support immunity

-

Reduce infections

-

Enhance nutrient absorption

Probiotic Strains, Dosage, Safety, and Supplement Guide

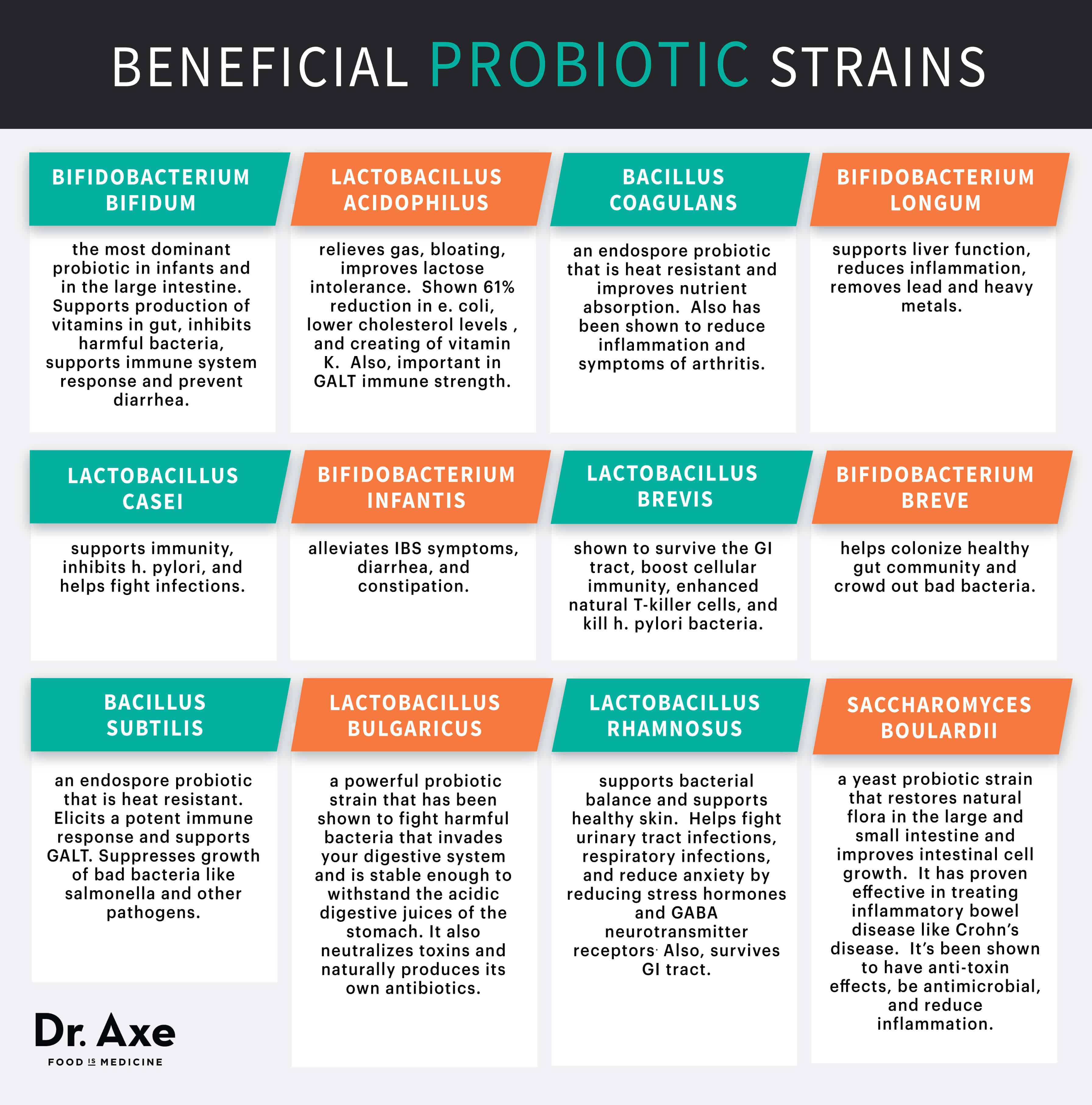

1. Understanding Probiotic Strains: A Professional-Level Comparison

Choosing probiotics by species (e.g., “Lactobacillus” or “Bifidobacterium”) is scientifically inadequate.

The strain determines the effect, not the species alone.

Below is a high-level strain comparison that reflects current clinical evidence.

1.1 Lactobacillus Strains

★ Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103)

One of the most clinically studied strains in the world.

Benefits include:

-

Strong protection against antibiotic-associated diarrhea

-

Supports immune system maturation in children

-

Reduces respiratory infections

-

Helps regulate the gut–brain axis in stress-related conditions

-

Broad safety across all age groups

Mechanisms involve adhesion to epithelial cells, toxin neutralization, and IgA enhancement.

★ Lactobacillus plantarum 299v

A highly resilient strain capable of surviving gastric acid and adhering to intestinal mucosa.

Clinically shown to:

-

Reduce IBS symptoms

-

Improve bloating and abdominal pain

-

Support nutrient absorption

-

Enhance anti-inflammatory signaling

Ideal for digestive health formulations.

★ Lactobacillus helveticus R0052

A psychobiotic strain used in combination with Bifidobacterium longum R0175.

Benefits include:

-

Reduced cortisol levels

-

Lower perceived stress

-

Improved emotional regulation

-

Better sleep quality

This pair is one of the most researched probiotic combinations for mental wellness.

1.2 Bifidobacterium Strains

★ Bifidobacterium infantis 35624

A key strain for immune modulation and gut barrier integrity.

Excellent for:

-

IBS (bloating, abdominal pain, hypersensitivity)

-

Inflammation-driven digestive symptoms

-

Pediatric gut health

★ Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12

One of the world’s most documented Bifidobacterium strains.

Evidence supports:

-

Improved stool regularity

-

Enhanced immunity

-

Reduced risk of respiratory infections

-

Better gut stability

★ Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001

Known for its effects on the gut–brain axis.

Shown to:

-

Improve emotional processing

-

Reduce visceral hypersensitivity

-

Support stress and mood balance

1.3 Saccharomyces Strains (Beneficial Yeast)

★ Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745

A unique probiotic yeast with strong resilience to antibiotics.

Supported uses include:

-

Prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea

-

Travel-related digestive issues

-

Restoration of microbiome after acute infections

-

Support during pathogenic exposure (e.g., C. difficile)

Saccharomyces does not colonize the gut but acts during passage, making it ideal for short-term protective protocols.

2. Dosage: How Much CFU Do You Really Need?

CFU (colony-forming units) represent the number of viable microorganisms in a probiotic dose. But more is not always better.

Different strains require different clinically effective dosages.

General dosage guidelines:

| Purpose | Typical CFU Range |

|---|---|

| Daily gut maintenance | 1–10 billion CFU |

| Mild digestive symptoms | 10–20 billion CFU |

| IBS / chronic gut conditions | 20–40+ billion CFU |

| Antibiotic-associated diarrhea | 10–20 billion CFU (with S. boulardii) |

| Immune support | 5–10 billion CFU |

| Women’s health (vaginal/urinary) | 5–20 billion CFU |

| Psychobiotics (stress/mood) | 1–3 billion CFU per strain |

| Children | 1–5 billion CFU |

Important note:

A high CFU count does not compensate for weak strain quality or poor survivability.

The strain matters more than the number.

3. Probiotic Delivery Systems: Why Some Work Better Than Others

Probiotic survival begins before the product reaches your gut.

The formulation must protect microorganisms from:

-

Heat

-

Moisture

-

Oxygen

-

Stomach acid

-

Bile salts

Here are the most common delivery technologies:

3.1 Enteric-Coated Capsules

Capsules with an acid-resistant coating that dissolves only in the intestines.

Advantages:

-

Protects against stomach acid

-

Ensures targeted delivery

-

Ideal for Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains

3.2 Microencapsulation

A more advanced technology where individual organisms are coated with a protective layer.

Benefits:

-

Higher survival rates

-

Better stability at room temperature

-

Enhanced shelf life

-

Improved performance in gummies and beverages

3.3 Freeze-Dried vs. Heat-Dried Probiotics

Freeze-dried (lyophilized):

-

Most stable

-

Best for supplements

-

Survive at room temperature

Heat-dried:

-

Cheaper

-

Require refrigeration

-

Less suitable for global distribution

High-quality brands always choose freeze-dried strains.

3.4 Gummies and Liquid Forms

Consumers love gummies, but probiotics in gummies are technically difficult because:

-

Gummies contain moisture

-

The heat during production can kill bacteria

-

Long-term viability is harder to maintain

That said, microencapsulation technology has improved gummy stability significantly.

Still, gummies typically offer lower CFU and fewer strain options.

4. Safety, Side Effects & Contraindications

Probiotics are generally considered safe for healthy individuals.

However, certain groups need careful attention.

4.1 Common, Mild Side Effects (Usually Temporary)

-

Gas

-

Bloating

-

Increased bowel movement frequency

-

Mild abdominal discomfort

These effects usually resolve after 3–7 days as the microbiome adjusts.

4.2 Who Should Be Cautious?

Probiotics may be risky for:

-

Immunocompromised patients

-

People undergoing chemotherapy

-

Individuals with central venous catheters

-

People with severe pancreatitis

-

Hospitalized critically ill patients

These groups should only take probiotics under medical supervision.

5. How to Choose a High-Quality Probiotic Supplement

Most consumers choose probiotics based on marketing claims, which leads to disappointment. A serious supplement brand or educated user should evaluate probiotics using the following criteria:

5.1 The Label Must Show the Full Strain Name

Not just Lactobacillus, not just L. rhamnosus — but the full strain ID, e.g.:

-

L. rhamnosus GG

-

B. infantis 35624

-

S. boulardii CNCM I-745

If the strain is missing, the product is not a scientifically validated probiotic.

5.2 CFU Guaranteed at Expiry (Not at Manufacture)

High-quality probiotics specify:

“X billion CFU at expiry.”

Poor-quality brands only guarantee CFU at the manufacturing date.

5.3 Delivery Technology

Choose probiotics with:

-

Enteric coating

-

Microencapsulation

-

Desiccant packaging

Avoid products with unclear stability claims.

5.4 Third-Party Testing

Top-tier supplements provide:

-

Microbial purity

-

Heavy metal testing

-

Pathogen screening

-

Shelf-life data

International markets often require COA (Certificate of Analysis).

5.5 Avoid “Kitchen-Sink Formulas”

Some brands add 20–30 strains with no evidence.

More strains ≠ better results.

A well-studied 3–6 strain formula often outperforms a random 20-strain blend.

Prebiotics, Synbiotics, Diet Interactions & Future Microbiome Science

1. Probiotics vs Prebiotics vs Synbiotics: A Complete Scientific Breakdown

Understanding the differences between probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics is essential for designing effective supplement formulations and guiding consumer expectations. Although the three are often marketed together, they perform entirely different biological roles within the gut ecosystem.

1.1 What Are Prebiotics?

Prebiotics are non-digestible fibers and compounds that selectively feed beneficial bacteria in the gut. Unlike probiotics—which are live organisms—prebiotics are substrates, meaning they act as the “food supply” for desirable microbes.

Examples include:

-

Fructooligosaccharides (FOS)

-

Galactooligosaccharides (GOS)

-

Inulin

-

Xylooligosaccharides (XOS)

-

Resistant starch

-

Certain polyphenols (e.g., from berries, green tea, cocoa)

Prebiotics enhance the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), especially butyrate, which is strongly linked to metabolic regulation, gut barrier function, immune balance, and even cognitive performance.

Key insight:

Prebiotics work slowly but powerfully. They are the foundation that sustains long-term microbiome health.

Without adequate fiber, probiotic supplements cannot perform optimally, because beneficial bacteria lack the fuel they need to colonize or influence the gut environment.

1.2 What Are Synbiotics?

Synbiotics combine probiotics + prebiotics in a single formulation that enhances the survival and expression of the probiotic strains.

There are two types:

Complementary synbiotics

Prebiotics support the growth of broader beneficial bacteria, not necessarily the exact probiotic strain in the product.

Example: L. plantarum + inulin.

Synergistic synbiotics

The prebiotic is specifically selected to support the growth or metabolic activity of the included probiotic strain.

Example: B. infantis + GOS (its preferred substrate).

Synbiotics can:

-

Improve colonization success

-

Increase SCFA output

-

Enhance stool regularity

-

Improve immune function

-

Support metabolic balance

-

Promote more stable microbiome changes

They are especially valuable for individuals with low dietary fiber intake, frequent antibiotic use, or chronic digestive issues.

2. How Diet Influences Probiotic Effectiveness

Probiotics do not work in isolation. Their effectiveness depends heavily on the dietary environment of the host. Diet determines the “soil” in which probiotics attempt to grow.

Here are the strongest diet–microbiome interactions supported by research:

2.1 Fiber Intake is the #1 Determinant of Microbiome Diversity

Populations with high-fiber diets (traditional African communities, Mediterranean diet followers) exhibit:

-

Higher microbial diversity

-

Greater SCFA production

-

Lower rates of metabolic disease

-

Stronger gut barrier integrity

When dietary fiber is insufficient, beneficial bacteria starve, leading to dysbiosis—even if someone is taking probiotics.

In other words:

A probiotic supplement cannot fix a low-fiber diet.

But in a high-fiber environment, probiotics flourish and produce significantly better results.

2.2 High Sugar & Processed Food Damage the Microbiome

Diets high in refined sugar and processed fats:

-

Reduce beneficial bacteria

-

Increase bile-tolerant, inflammation-linked microbes

-

Disrupt gut-brain axis signaling

-

Promote leaky gut

-

Increase risk of dysbiosis-related conditions

Even the best probiotic strains cannot permanently counteract dietary inflammation if the baseline diet remains highly processed.

2.3 Fermented Foods vs Probiotic Supplements

Fermented foods (yogurt, kefir, kimchi, kombucha, sauerkraut, miso, tempeh) contain live microbes, but:

-

The strains rarely match clinical probiotic strains

-

The CFU counts vary dramatically

-

Many microorganisms cannot survive stomach acid

-

Effects are milder and less targeted

Fermented foods support overall microbiome diversity and dietary richness—but do not replace clinically validated probiotic supplements.

3. How Long Do Probiotics Take to Work? A Realistic Timeline

Many consumers expect probiotics to work within days, but the actual timeline depends on several factors:

3.1 Short-Term Effects (0–2 Weeks)

Users may experience:

-

Mild digestive changes (gas, shifting bowel habits)

-

Improved stool regularity

-

Reduced bloating

-

Better tolerance to certain foods

These changes reflect early microbial interactions and adjustments.

3.2 Mid-Term Effects (3–6 Weeks)

Probiotic benefits become more noticeable:

-

Reduced IBS symptoms

-

Lower frequency of digestive flare-ups

-

Enhanced immune resilience

-

Improved vaginal microbiome stability

-

Better mood stability and stress response

This phase reflects stabilized colonization and immune modulation.

3.3 Long-Term Effects (2–6 Months)

Deep, microbiome-driven changes:

-

Higher microbial diversity

-

Stronger gut barrier

-

Improved metabolic markers

-

Reduced systemic inflammation

-

More stable mental and emotional wellbeing

-

Long-lasting improvements in digestion

These effects require consistency and supportive diet patterns.

4. Future Directions in Probiotic & Microbiome Science

The probiotic field is rapidly evolving. The next decade will introduce revolutionary advancements far beyond the current generation of supplements.

4.1 Precision Probiotics (Strain-Level Personalization)

Genomic sequencing allows researchers to identify highly specific strains tailored to individual microbiome profiles.Future probiotics will be personalized, rather than universal.

4.2 Postbiotics: The Next Generation of Microbial Therapies

Postbiotics are non-living microbial products, including metabolites, enzymes, peptides, and cell fragments.

They offer advantages:

-

No survivability issues

-

Highly stable

-

Clear mechanisms

-

Strong immune-modulating effects

Postbiotics may soon surpass traditional probiotics in certain therapeutic uses.

4.3 Live Biotherapeutics (LBPs)

LBPs are pharmaceutical-grade microbes designed as regulated drugs, not supplements.

They target conditions such as:

-

Ulcerative colitis

-

Crohn’s disease

-

Antibiotic-resistant infections

-

Metabolic disorders

This field will redefine how we use microorganisms for medical therapy.

4.4 Microbiome-Based Mood & Cognitive Therapies

“Psychobiotics” will expand into:

-

Anxiety and depression support

-

Sleep optimization

-

Cognitive performance enhancement

-

Neuroinflammatory condition management

Early research is highly promising.

4.5 Microbiome & Longevity Research

Emerging studies suggest the microbiome influences:

-

Aging rate

-

Muscle maintenance

-

Hormone balance

-

Inflammation (“inflammaging”)

-

Age-related diseases

Future probiotics may become core components of anti-aging strategies.

5. Final Summary: What Probiotics Truly Offer

Probiotics are not magic pills—but when chosen properly, supported by diet, and taken consistently, they provide profound benefits backed by decades of scientific research.

A truly high-quality probiotic strategy involves:

-

Strain specificity

-

Adequate CFU

-

Strong delivery technology

-

Prebiotic support

-

Personalized selection

-

Long-term consistency

-

Evidence-based expectations

The microbiome sits at the center of human health—digestive, immune, metabolic, mental, and even skin wellbeing.Supporting it with targeted probiotics is one of the most powerful, science-backed ways to improve long-term health.

Reference list

1. FAO/WHO Guidelines on Probiotics

FAO/WHO. (2002). Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food.

https://www.fao.org/3/a0512e/a0512e.pdf

2. NIH – National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH)

Probiotics: What You Need to Know

https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/probiotics-what-you-need-to-know

3. ISAPP – International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics

Consensus statements & scientific resources

https://isappscience.org

4. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103)

Szajewska H. et al., The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2015.

PubMed index: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25547277/

5. Lactobacillus plantarum 299v – IBS Research

Johansson ML et al. Clinical study on IBS.

PubMed search: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Lactobacillus+plantarum+299v

6. Bifidobacterium infantis 35624

Whorwell PJ et al., Gastroenterology, 2006.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16401471/

7. Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745

McFarland LV, Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Saccharomyces+boulardii+CNCM+I-745

8. Psychobiotics: L. helveticus R0052 & B. longum R0175

Messaoudi M. et al., British Journal of Nutrition, 2011.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21736802/

9. Gut–Brain Axis Research – Cryan & Dinan

Foundational studies:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Cryan+Dinan+microbiome

10. Infant Probiotic Research (B. infantis)

UC Davis Human Milk & Lactation Research Center

https://hmnb.ucdavis.edu

11. Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 for Infant Colic

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Lactobacillus+reuteri+DSM+17938

12. Women’s Health – GR-1 and RC-14 Strains

Reid G. et al., Journal of Infectious Diseases.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Reid+GR-1+RC-14

13. Metabolic Health – Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Lactobacillus+gasseri+SBT2055

14. Bifidobacterium breve B-3

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Bifidobacterium+breve+B-3

15. Intestinal Barrier & SCFA Research

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=SCFA+gut+barrier

16. EFSA (European Food Safety Authority)

Qualified Presumption of Safety list

https://www.efsa.europa.eu

17. FDA GRAS Notices for Probiotic Ingredients

https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras

18. ClinicalTrials.gov – Probiotic Clinical Trials

https://clinicaltrials.gov

19. PubMed – General Probiotics Database Search

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=probiotics